When I was growing up in Salem, I lived in a little red house with a view out of our kitchen window to Mount Jefferson. Looking out this window, I wondered what there was to see in the mountains out there. In time, I got to explore this region extensively as a teenager, and I came to know the Opal Creek and Mount Jefferson regions quite well.

The author in Jefferson Park in 1996.

I moved away when I was 16, and returned for graduate school at age 24, this time settling in Portland. I very soon returned to the area in which I grew up, and fell in love all over again. Over time, I ended up writing a guidebook to this area, titled 101 Hikes in the Majestic Mount Jefferson Region. You can read more about it on this website!

When the Lionshead, Beachie, and Riverside Fires ravaged the Majestic Mount Jefferson Region in 2020, it was a blow that felt especially devastating during the COVID-19 pandemic. The widespread devastation of the area continues to reverberate to this day, with news that the entire region will remain closed through 2022. With my favorite places closed over the past two years, I explored other regions, and found new favorite places to play. But my heart remained in the Majestic Mount Jefferson Region, and in time, I developed a new hobby: collecting historical photos and postcards of the region. What follows here is a historical exploration of the Majestic Mount Jefferson Region, or if you will, the Sensational Seekseequa Region.

On that note, here are two important points to make:

Everything you will see here in the Mount Jefferson (Seekseekqua) area is on the historic and ancestral lands of the Tenino, Molalla, and Warm Springs tribes. For more information, see the Native Lands Project.

As these photos were taken before I was born, I am obviously not the photographer. I am sharing these photos in the public interest, but if you believe these photos are still copyrighted, please contact me and I will be happy to remove a photo if requested.

With that in mind, let’s get exploring!

Mount Jefferson and “Hanging Valley”, circa 1907

Even as early as the beginning of the 20th Century, Mount Jefferson was a popular photography location. The photo you see here is looking down into Jefferson Park, then known as Hanging Valley. This was the earliest photo I could find of the area. Access to the area was exclusively on foot (or on horseback), as reflected in this photo of two men hiking the Bagby Trail on the slopes of Battle Ax in August 1930:

Take a minute and imagine how much effort it took to travel in the Majestic Mount Jefferson Region some 100 years ago! Over the next few decades, it became much easier to access the Majestic Mount Jefferson Region, and many more people were able to explore this most magical of places.

The caption reads: Mt. Jefferson from Hanging Valley, Oregon

By the 1930s, Jefferson Park was still referred to as “Hanging Valley”, but it would not be so for much longer. There is so much to note here! First of all, this looks like Bays Lake, but it could also be Scout Lake. Second of all, note the size of all both glaciers visible in the photo, especially the Russell Glacier on the right. Today the glacier is still visible, but is mostly out of sight in the shadow of the mountain’s summit. Here though, it’s a massive river of ice that reaches all the way down into the park. I would have loved to see it!

This photo was taken on August 6, 1936.

Sometime during the summer of 1934, a debris flow surged down from the Whitewater Glacier and into the eastern end of Jefferson Park. Two years later, the debris flow was still an obvious landmark, which this photo depicts. Even today, you can see evidence of it from Park Ridge if you look at the eastern end of the park.

Other areas were becoming easier to reach, as well. The Skyline Road was constructed along the crest of the Cascades between Government Camp and Breitenbush Lake, and a road was constructed to Breitenbush Hot Springs, allowing automobile access to the area for the first time. I was able to find a pair of photos from the early 1930s of the Breitenbush area:

The road from Detroit to Breitenbush circa 1932; today this road is paved and is known as Forest Road 46.

A photo of South Breitenbush Gorge circa 1932. The Gorge was a popular hiking destination until 1990, when a massive windstorm blew down dozens of trees in the area, making it much more difficult to see the Gorge.

With new roads being built, many more opportunities developed to explore the Majestic Mount Jefferson Region. One such road was known as Oregon Highway 222, a precursor to both Oregon Highway 22, and Forest Road 46. You can find 222 on old maps, and it’s fun to imagine an alternate history in which Forest Road 46, which runs from Estacada to Detroit, became the primary highway through the Cascades instead of US 20. As it is, the road led to some absolutely spectacular views. If you’ve ever driven from Estacada through Detroit and stopped at Breitenbush Pass to take in the view of Mount Jefferson, here’s what it looked like in the 1940s:

Mount Jefferson from Breitenbush Pass circa 1940. The sharp, stubby peak to the right of Mount Jefferson is Dynah-Mo Peak, though it would not be named as such until the 1980s.

This view is no longer available for a variety of reasons. First and foremost, this area burned during the Lionshead Fire, as well as during the Whitewater Fire in 2017. But second of all, the power lines that run through the Breitenbush Pass area obscure this view from the road. I’ve tried over and over again to find a similar view to this over the years, and I’ve never succeeded. I am very curious to see what this area looks like when it opens up again, but I’m not expecting much.

Other areas of the Majestic Mount Jefferson Region would become easier to explore, as well. Here’s a photo of Mount Jefferson from the east, on what is now the Warm Springs Reservation:

Mount Jefferson from the east, circa 1940. You can see in the foreground how arid the land was even then, so it’s unsurprising that this area has burned repeatedly as the climate warms. You can also see that the Whitewater Glacier, which drapes the eastern slopes of the mountain, was even more impressive then.

This is an interesting photo for several reasons, but most of all, because it depicts a view that is now lost to time. Unless you’re a member of the Warm Springs Tribe, you cannot visit this spot, and almost everything in the foreground of this area has burned in recent times.

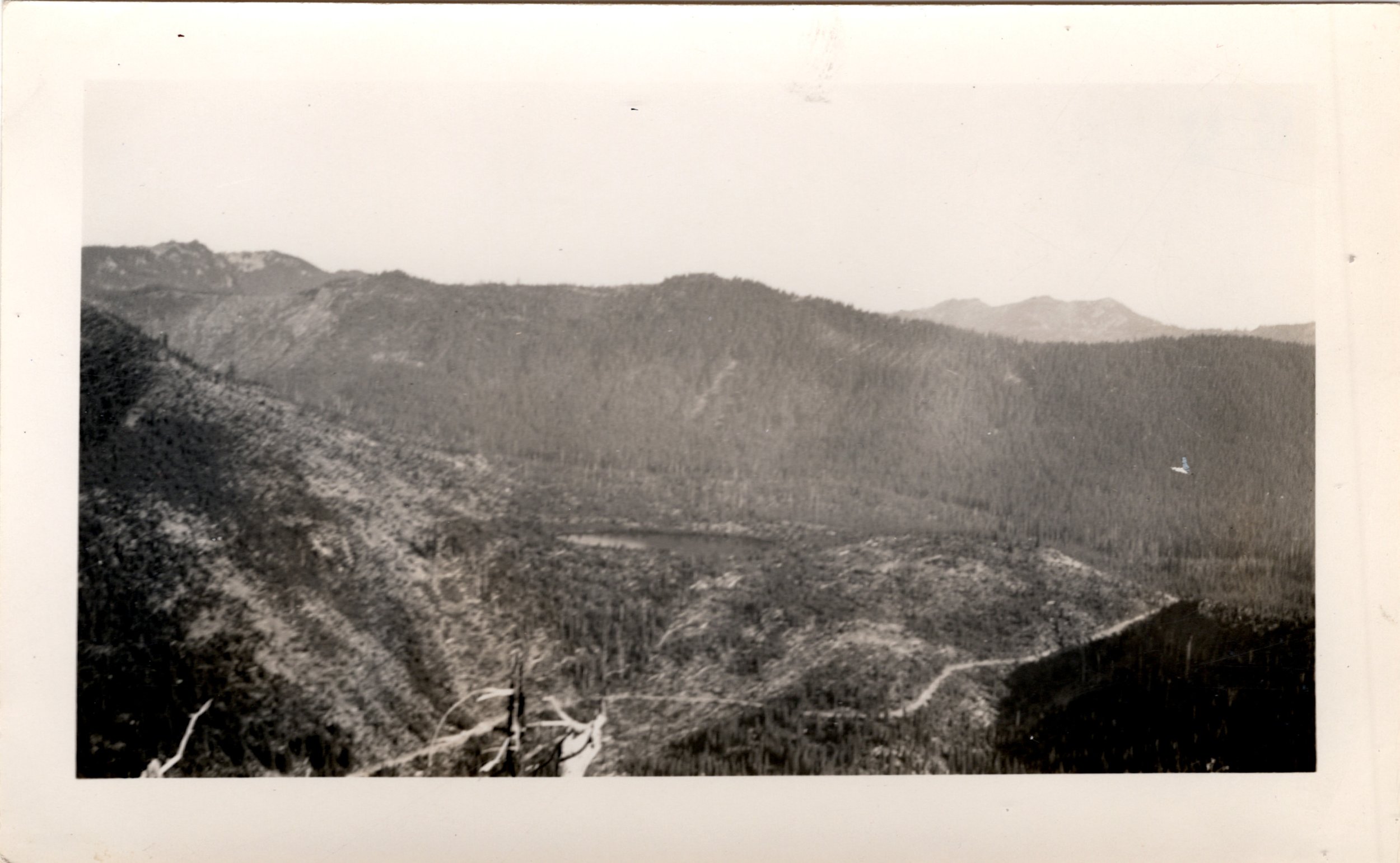

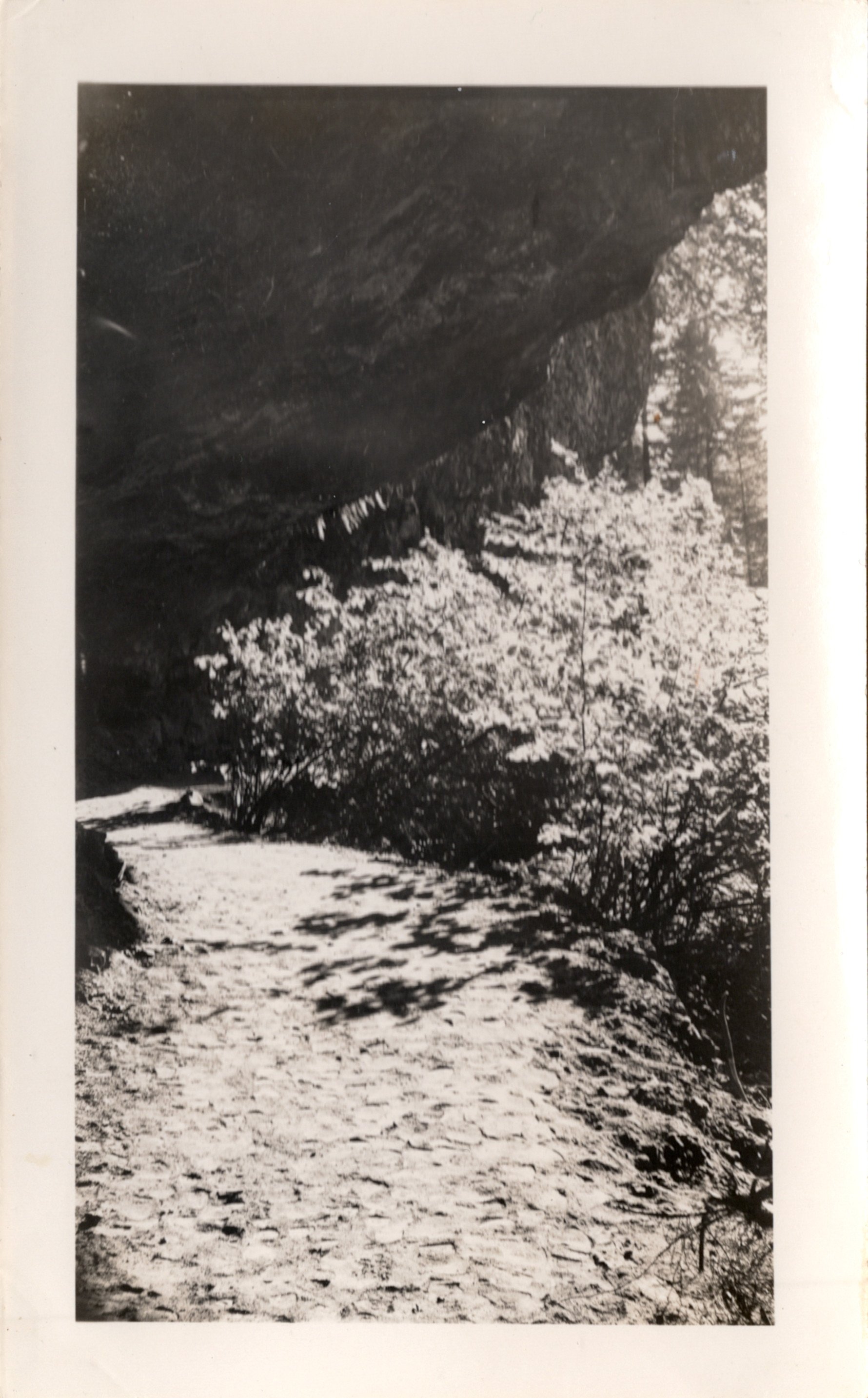

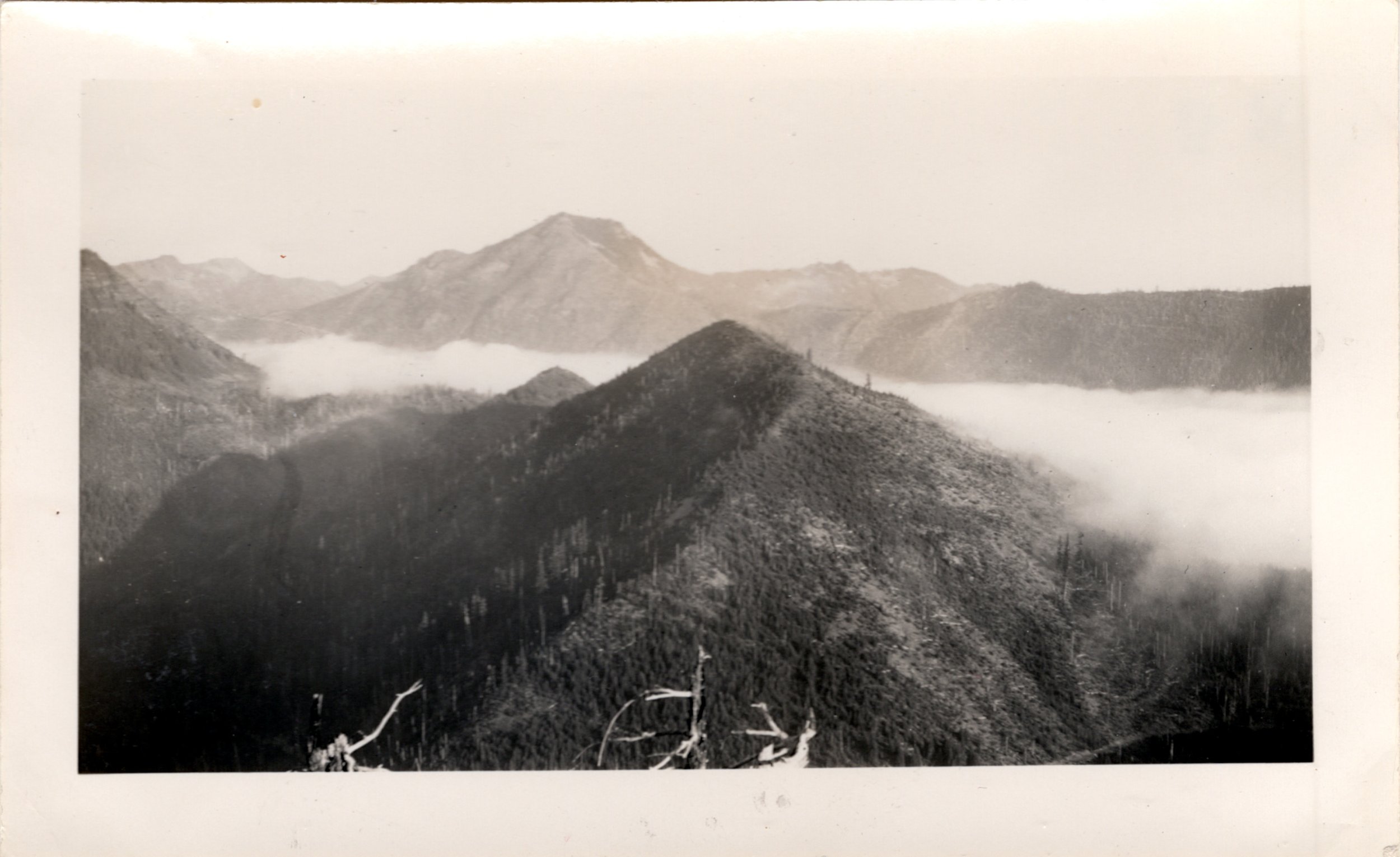

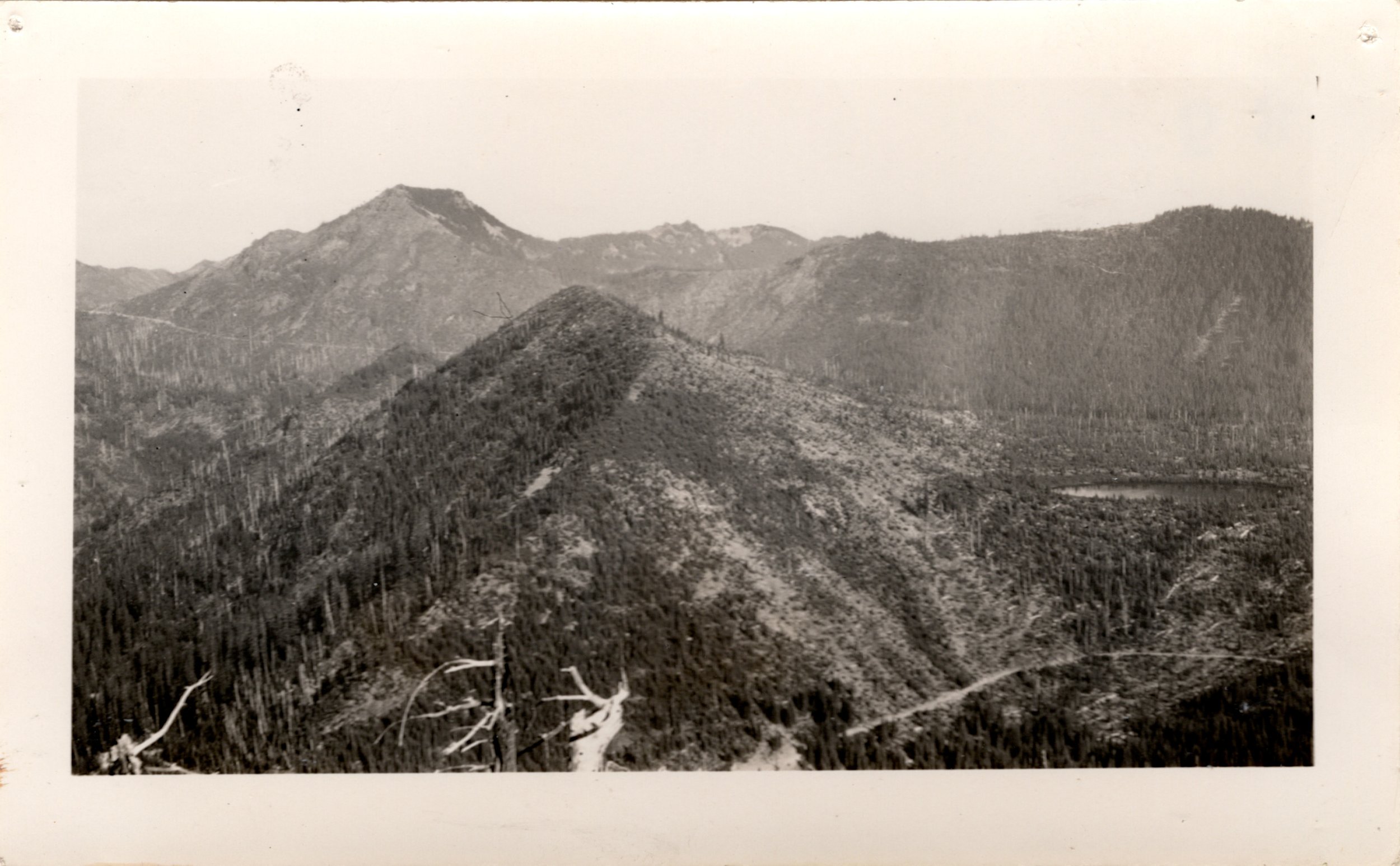

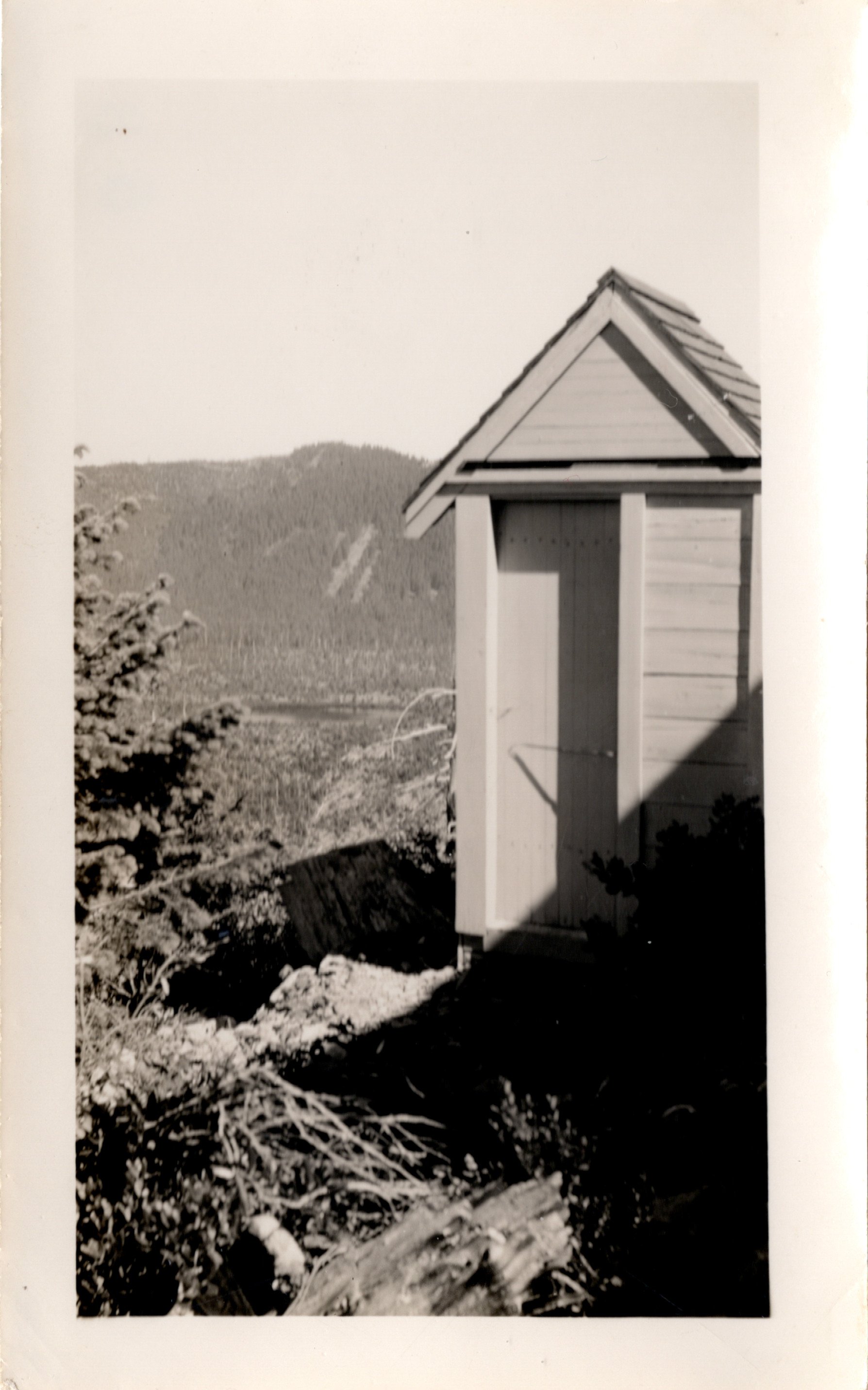

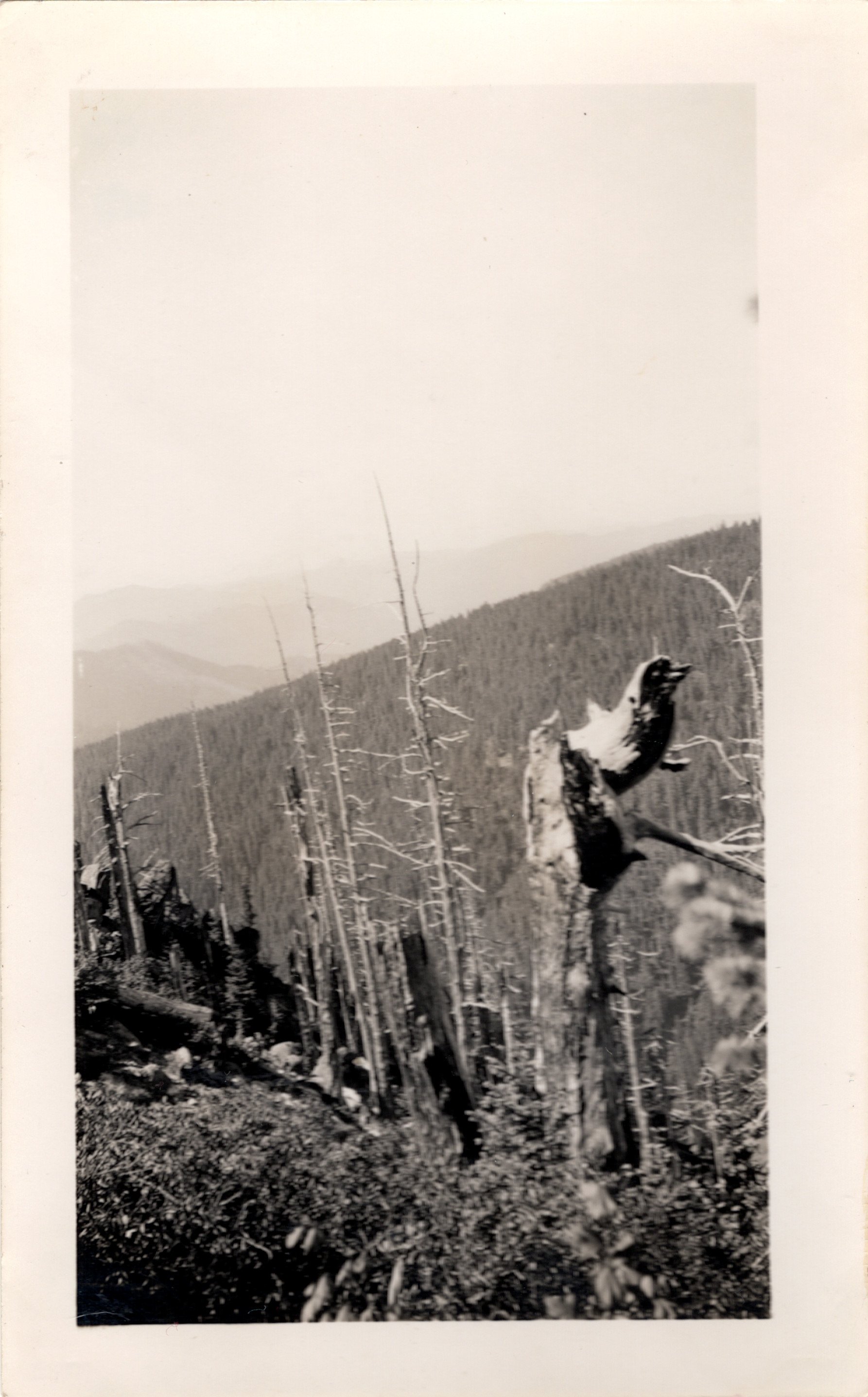

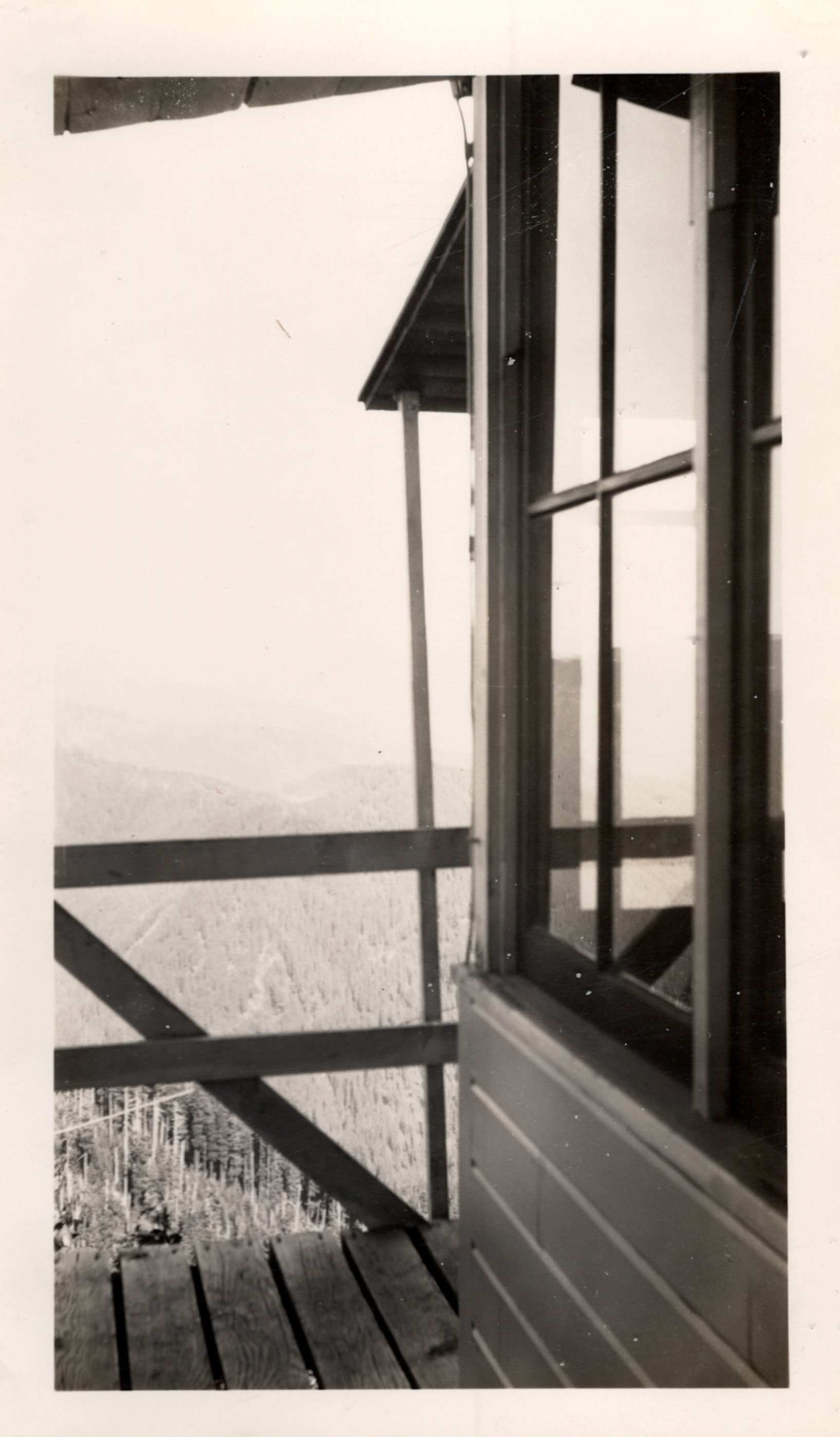

On the west side of the Majestic Mount Jefferson Region, trails and roads were built all over the mountains and through the ancient forests that blanketed the western slopes of the Cascades. I bought an unlabeled collection of photos, which I determined were taken at the Gold Butte Lookout sometime in the 40s or 50s:

These aren’t the greatest photos you’ll ever see but it does give you a good idea of what it would have been like to work a lookout tower back in the 40s and 50s. I only wish the mountain views were better in these photos. So instead, here’s one more postcard of Jefferson Park, this time from the 1950s:

A postcard of Mount Jefferson and Jefferson Park from the 1950s. Note the location of the debris flow on the eastern end of Jefferson Park, still easily visible in this photo.

That there, that’s one of my favorites. This is Mount Jefferson how I will remember it. Here is a photo I took in almost the same spot, some 60 years later:

Mount Jefferson and Jefferson Park, August 2016.

What is remarkable about these two photos is how everything looks essentially unchanged in the photo from 2016. This is not to say that nothing changed, of course; but looking at the two, I see almost no difference. But obviously, this last photo was taken before the Whitewater and Lionshead Fires burned over this area. While Jefferson Park was mostly spared from the worst effects of both fires, it will still look very different in the future.

My collecting was not limited to the Majestic Mount Jefferson Region; I also bought a few photos from other spots that interested me. For instance: did you know that Mount Hood (Wy’east, located on the traditional lands of the Multnomah tribe) briefly had a lookout on its summit? Here’s photographic proof:

Can you imagine staffing this building? It boggles the mind!

The lookout on Mount Hood only stood for some dozen years in the 1920s and 1930s. It is hard to believe that such a structure was ever built in the first place, but summiting the mountain was said to be easier during this time period and the lookout was only staffed for several weeks during the summer.

Speaking of Mount Hood, I had to also purchase this postcard when I saw it:

Don’t try this at home!

Another truly amazing photo that I purchased gives you an idea of what the glaciers must have looked on Mount Hood in the 1920s and 1930s:

Wow! Again, don’t try this at home!

What a sight this must have been. The Eliot Glacier is still there, of course, and can be seen from the Cooper Spur Trail - but seeing this is another level of spectacular that I had never imagined.

Speaking of Mount Hood, here’s a photo of Lost Lake from the 1920s or early 1930s:

Lost Lake from about 100 years ago.

Lost Lake looks almost exactly the same now, as this area has not burned since then. There is one major difference, however; note the massive size of the Sandy Glacier, left center on Mount Hood. This glacier has shrunk significantly in recent times, as have all glaciers on Mount Hood (and almost everywhere else). Aside from that though, it is with great joy that I can say that this view is still the same.

From this same photo set comes a photo of one of Oregon’s most famous places:

Oneonta Gorge in the 1920s.

Maybe some of you recognize the place? Oneonta Gorge (located on the traditional lands of the Cowlitz tribe) was one of the most popular and famous hikes in Oregon until the 2017 Eagle Creek Fire. It was a summer tradition to hike up the narrow canyon to the waterfall at the end of the canyon, something I did a few times myself. I have a similar photo to this:

Oneonta Gorge, August 2014.

Speaking of waterfalls and narrow gorges, I could not resist buying this photo of Lemolo Falls (located on the traditional lands of the Molalla and Modoc tribes) in southern Oregon, taken sometime in the 1940s:

Lemolo Falls during the 1940s.

If you’ve ever seen a photo of the falls, you know how impressive it is. And yet, this photo is so much more impressive, as it was before much of the flow of the North Umpqua River was diverted out of the river and into the pipes and dams so ubiquitous in the area. I finally visited Lemolo Falls this past fall, and here’s a photo from almost this same spot:

Lemolo Falls, October 2021

Last but not least, while I primarily bought old postcards and photos of the Majestic Mount Jefferson Region and a few other things that caught my eye, I absolutely had to buy a photo of Spirit Lake and Mount Saint Helens (Loowit, located on the traditional lands of the Klickitat and Cowlitz tribes) from before the eruption:

Mount Saint Helens in the 1930s.

To see Loowit before the eruption must have been incredibly special. I can see why there are people who have not been back since the eruption. Speaking of which, I also bought this incredible photo of this same area taken only a few months after the May 1980 eruption:

All I can say about this photo is WOW. I feel grateful to own this photo, and looking at gives me chills. Here is the full force of nature on display, and its most ferocious and awe-inspiring. I first visited the Loowit area in the late 1980s and it still looked a great deal like this, and it is fascinating to see how the area is regrowing and regenerating in the decades after the eruption. I can only hope to see the same process play out in the areas that burned in the fires over the past decade.

Documenting the history of some of my favorite places became a fascinating and delightful distraction throughout the pandemic. Look for more photos to be added to this page in the future!

Thanks for reading.

Matt

January 2022